Trust Us, it’s P91

At one of the world’s most spectacular power-desalination facilities, the systemic weld defect discovery resulted in a soul-crushing realization that some contractor’s self-interest has no moral boundary. If they think they can get away with something, they will certainly try, regardless of the impact to a client/owner and even themselves. Even more troubling, there really is little financial gain with some of these actions.

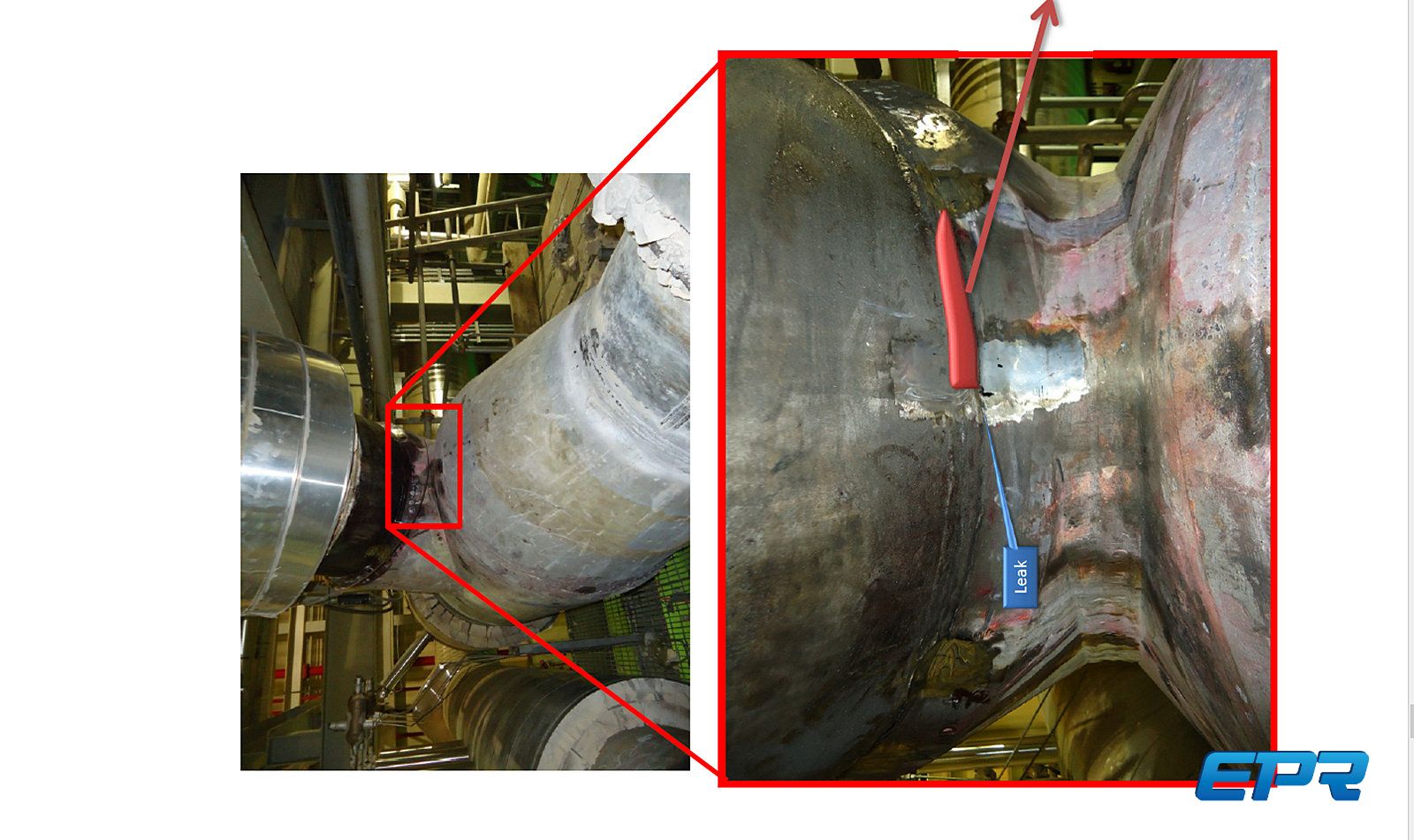

What started as an investigation into welding defects not properly identified in QC documentation, evolved quite dramatically when a P91 (9% Cr) hot reheat steam piping failed radially at a fabricated wye (fitting) near a steam turbine. Luckily, the failure was not catastrophic, being about 12” long, and allowed a prompt orderly unit shut down with no injury.

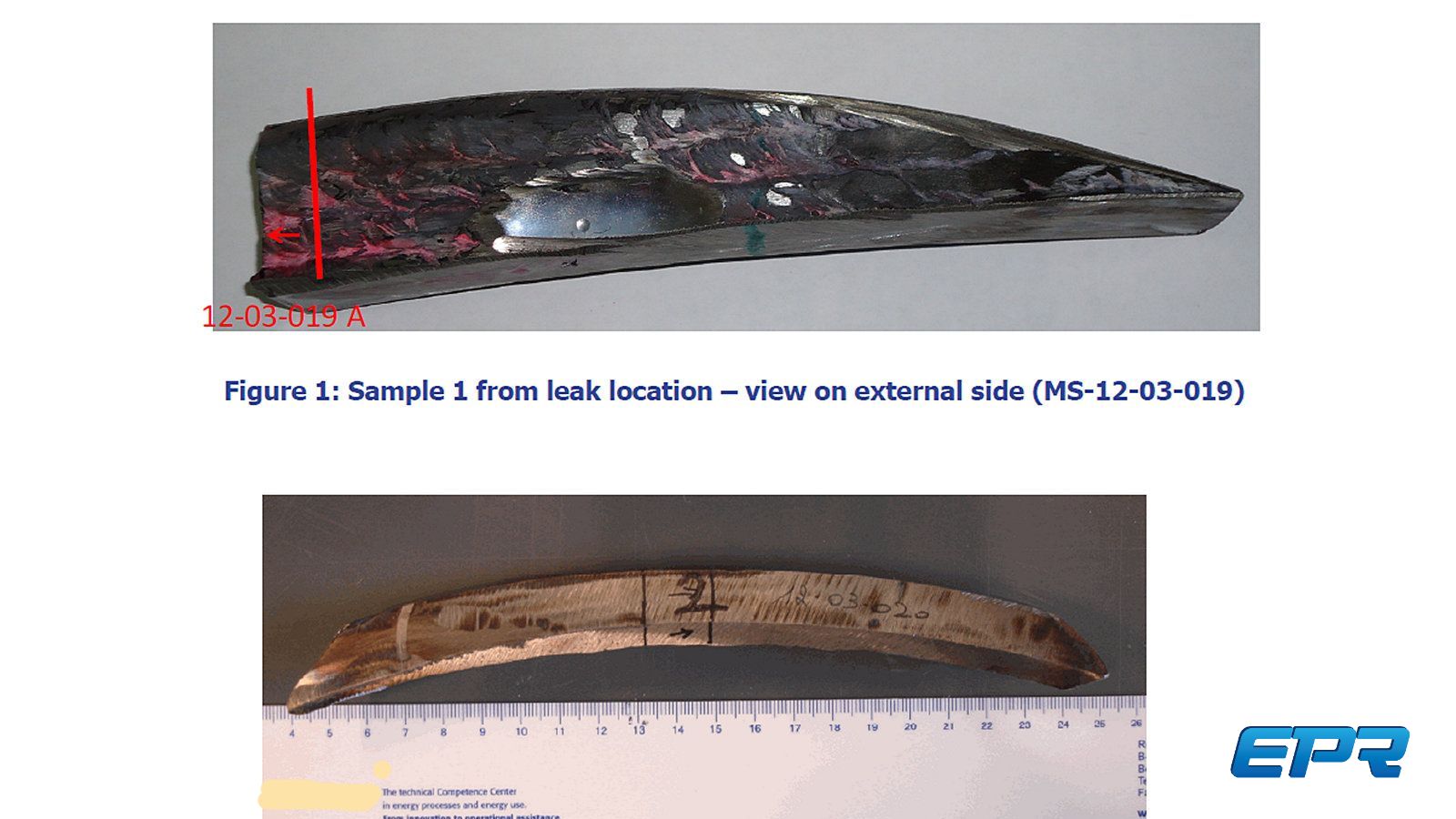

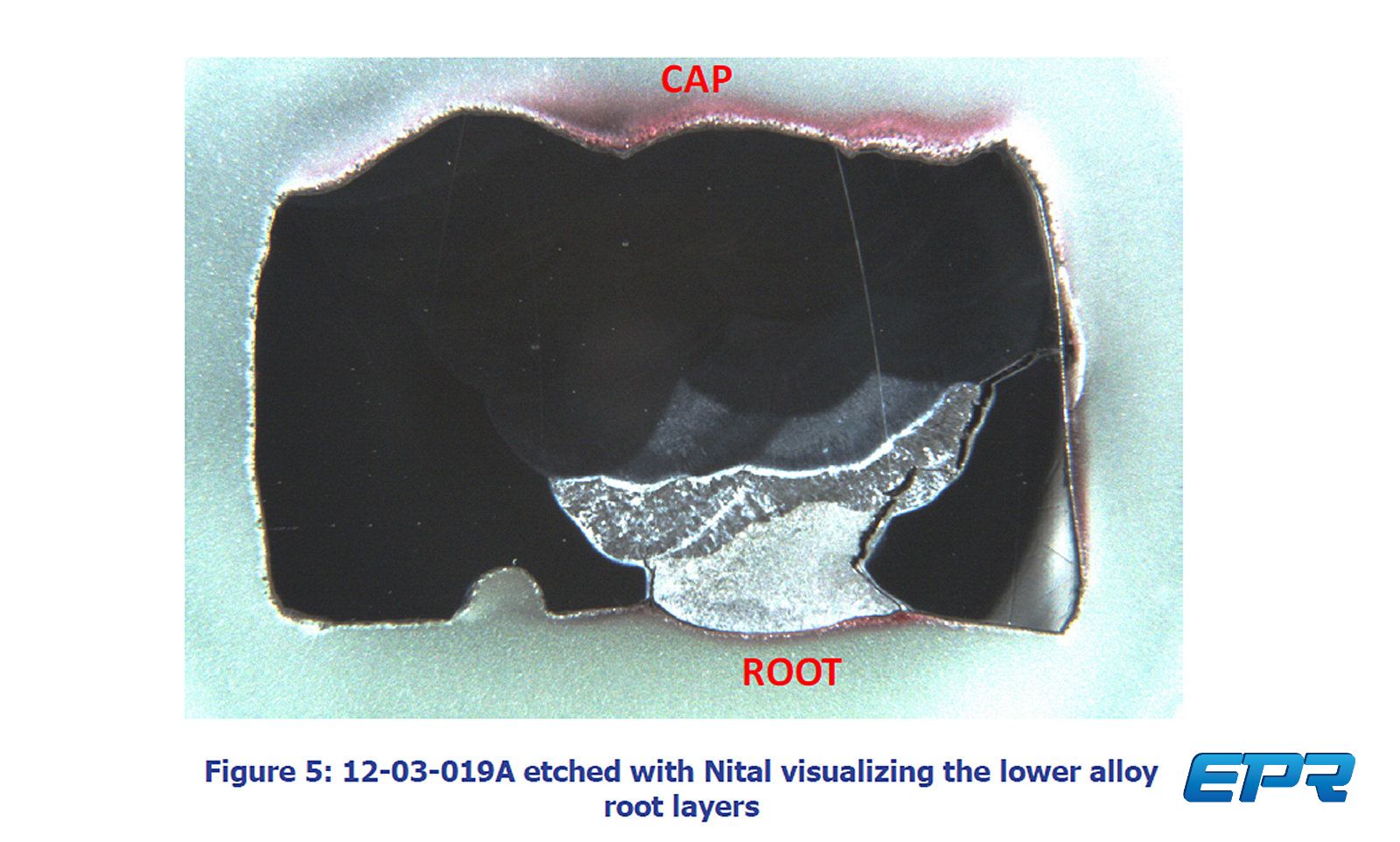

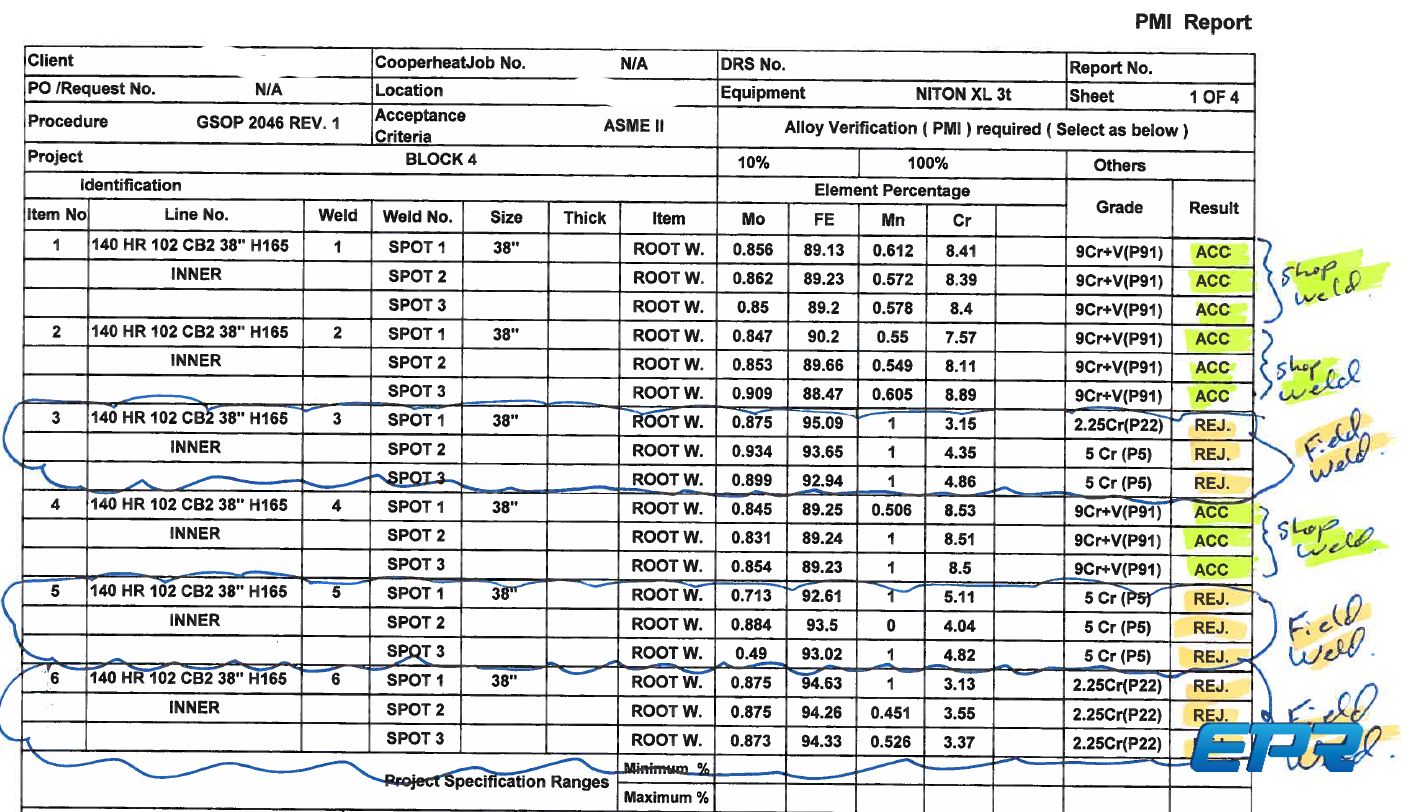

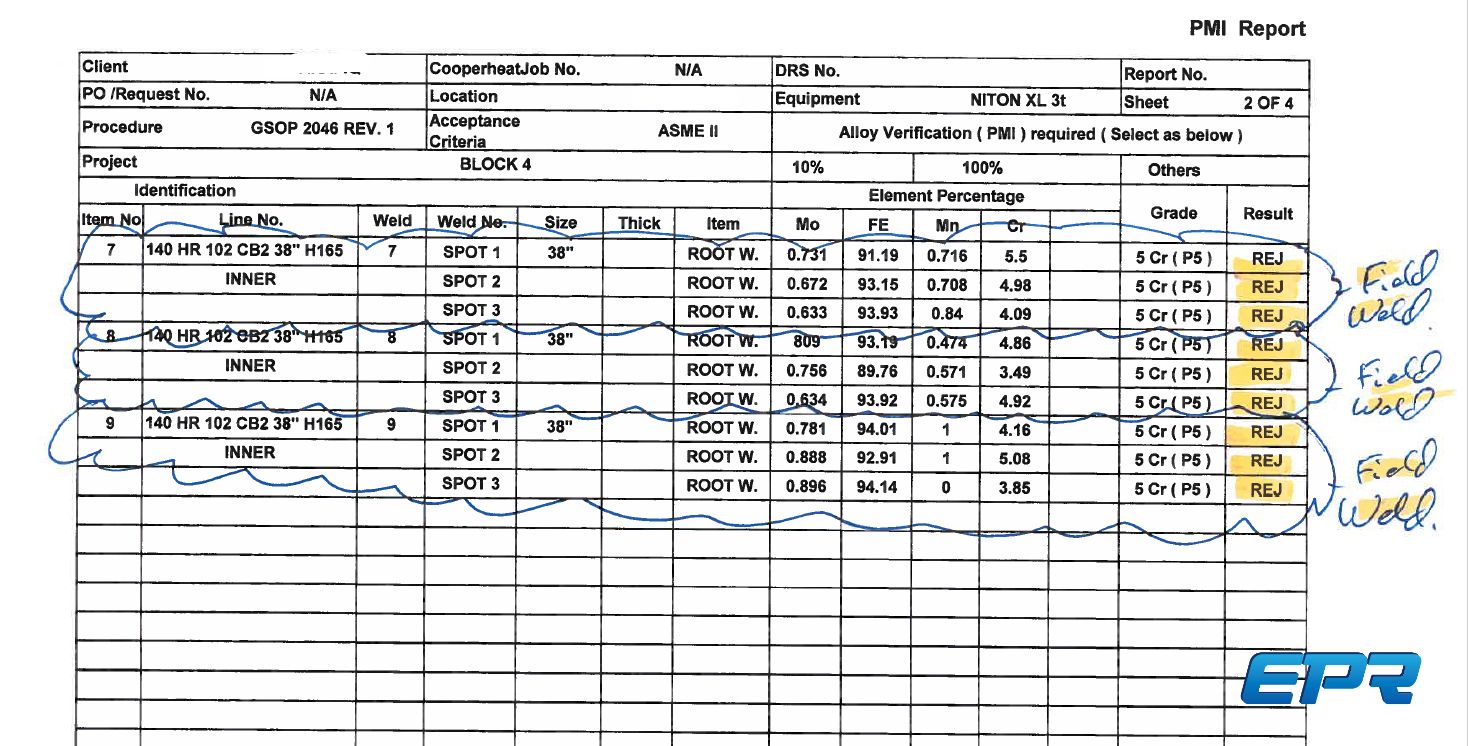

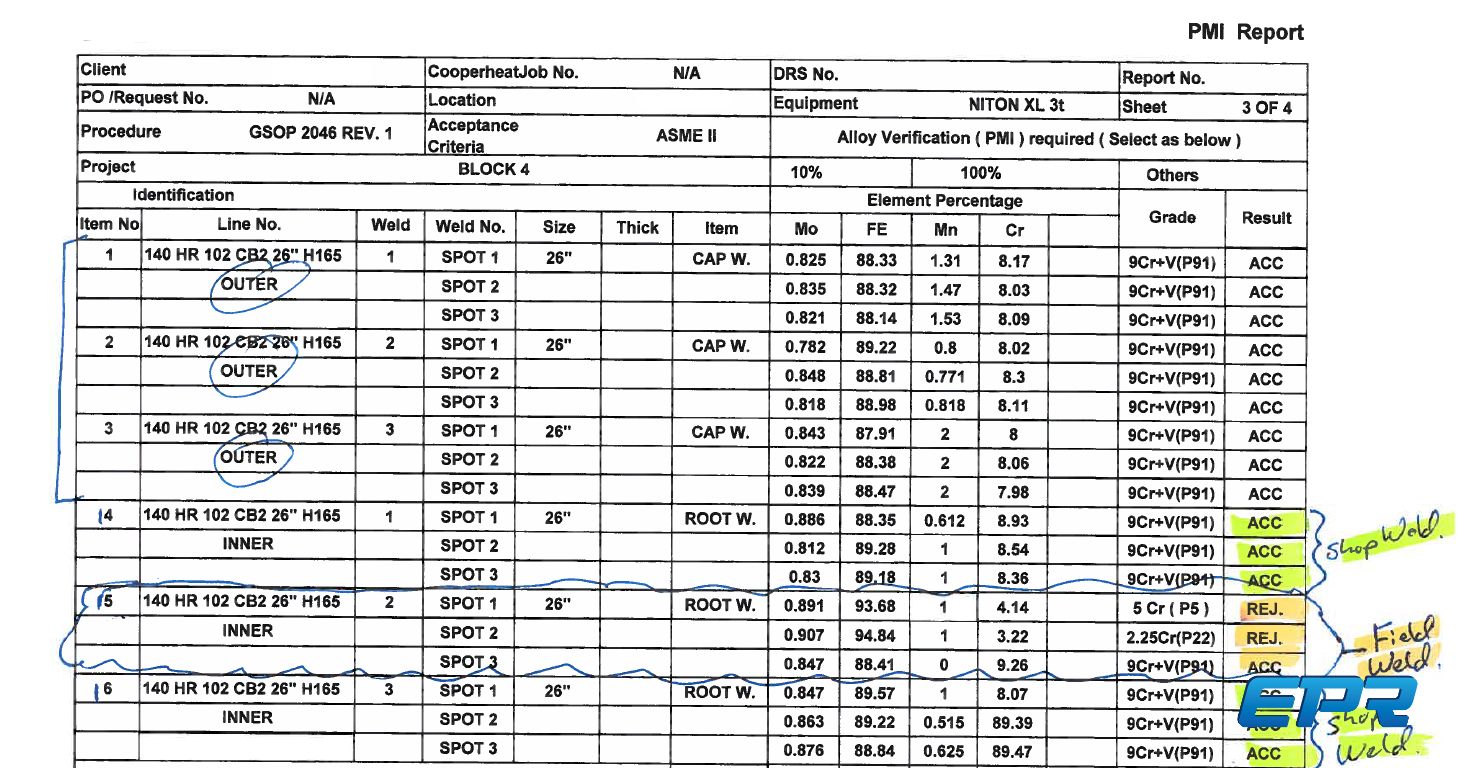

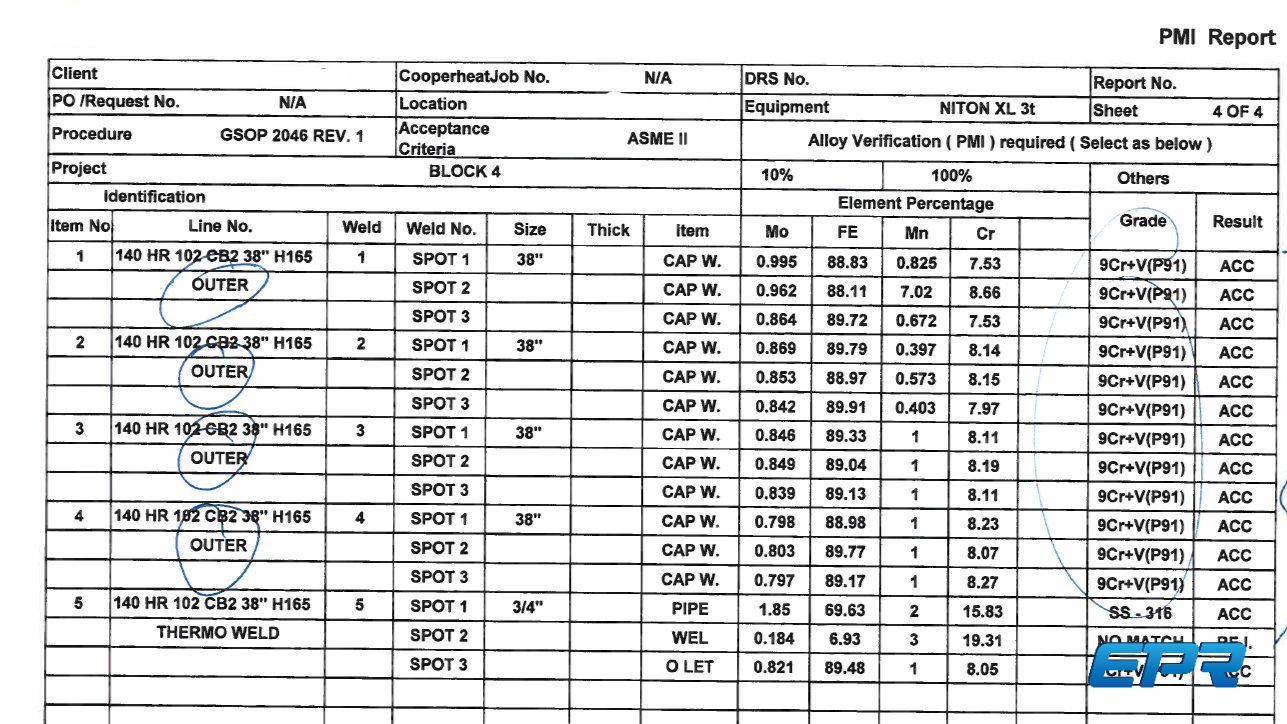

The fitting was cut out, and boat samples of the crack area were sent to a contractor lab and owner lab for metallurgic analysis. In the meantime, the head scratching started. It was clear early that the weld records had issues, this was visible internally. However, while waiting for metallurgy results, a third-party testing firm was engaged to perform PMI (positive metal indication). Since much external insulation had been removed and the piping was open (30” diameter), it afforded an opportunity to test weld caps, weld roots, and base metal to be sure everything was to specification. The expectation was for routine testing…

When the inspection firm showed up, the EPC contractor staff become hysterical and essentially put a dozen bodies in front of the open pipe to dissuade and argue that none of this was necessary. But it wasn’t their call. They were invited to participate, but once it was clear PMI testing would proceed, they left as fast as possible. What happened next, they already knew…

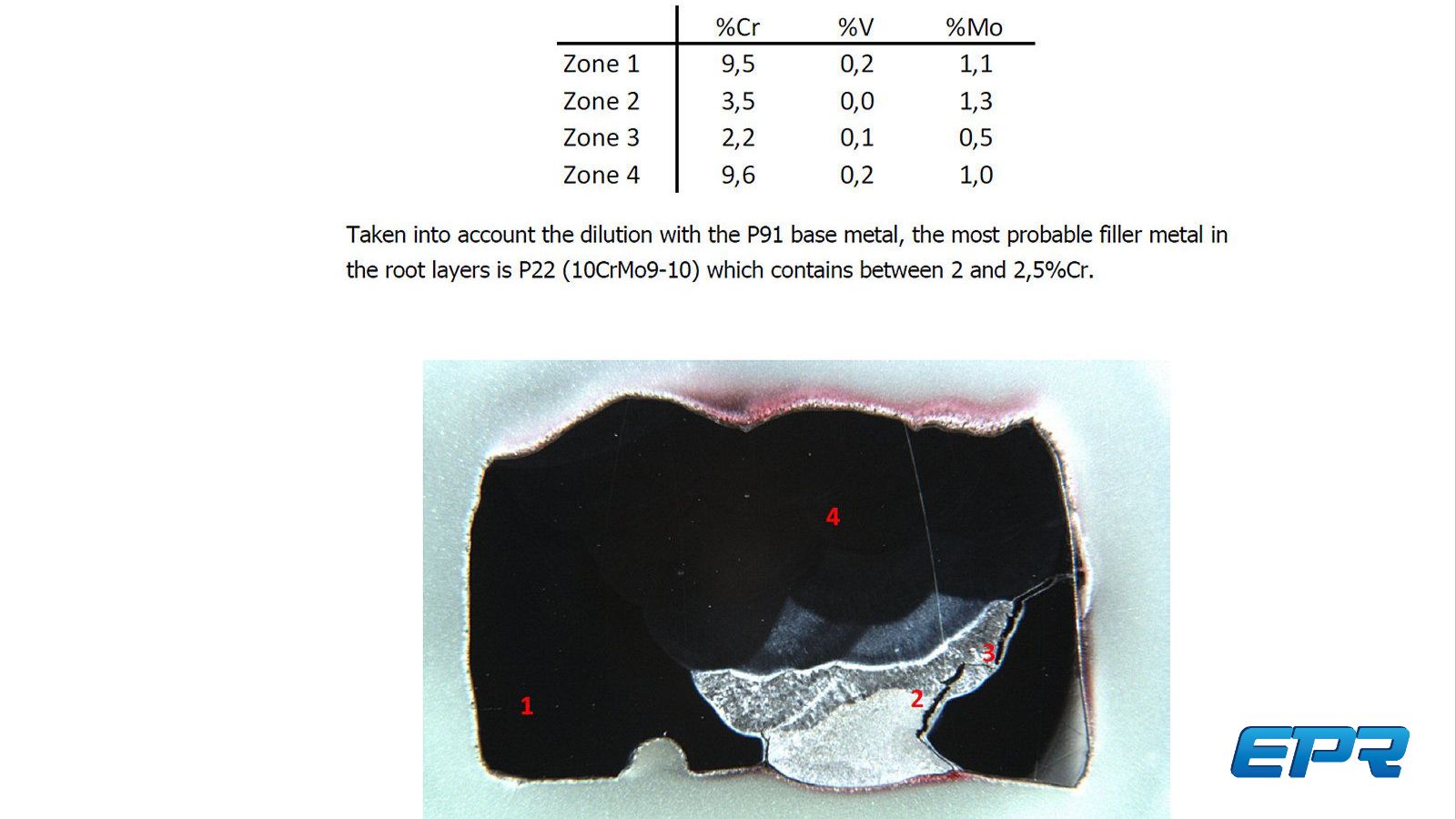

Upon inspection, all the field weld roots (ID) which are normally not accessible, had P22 (2% Cr) filler in the roots, and P91 caps (9% Cr) to match the base metal which tested as acceptable. At the same time, all the shop welds were fine with P91 root filler. To be clear, there really was not exception to this finding; all the shop welds were as specified, all the field welds were not, being P22. For those not familiar with welding technicalities, a P91 system with P22 filler should expect creep failure in about 4.5 years, not the life of the plant.

So, this opened a whole new raft of concerns and questions. How extensive was this issue? Well, it ended up being all the large-bore P91 in the whole plant. As it turned out, the metallurgy analysis of the failure eventually showed P22 root filler was a major contributing factor to accelerated creep and failure of the weld. There were other factors like excessive post-weld heat treating (PWHT) and probably joint cyclical stress. However, none of that really mattered once it was determined that the EPC contractor had systematically cheated on the critical pipe welding program.

Maybe it was an honest mistake?

The contractor held relevant ASME stamps and had qualified ASME processes. This includes things like rod control during procurement, receiving inspection, field rod control, and lastly by the welder himself. Each weld rod is marked clearly so everyone knows the details of the filler. QC staff are supposed to be performing checks, and a number of other layers of double checks to assure there is not a single instance where a welder grabs a filler not specified for the given weld procedure he’s working to. As a side note, EPR found dozens of old stubs clearly identified as P22, when incidentally there was no weld procedure approved using P22 (P11 and P91 only), so why was an P22 filler even on the project site.

Normally, in cases where there are mistakes discovered with the use of incorrect filler, it becomes a very big issue and stops most work until the procedural deficiencies and extent of the error become known and dispositioned. So, jump from that “normal problem” to a situation where an entire plant has the wrong filler in the root, but not in the cap (the visible part) leads to the only conclusion possible. The contractor deliberately cheated.

What motivation could there be for such a breech. Well, the contractor can use less experienced welders that are probably cheaper (P91 is hardest to weld and to qualify). There are production advantages with less rework. The other savings is possibly less inert gas to purge inside piping when not welding P91. Regardless, compared with the immense consequences to both the owner and contractor, this behavior defies any rational explanation of motive.

This issue was just one of thousands for this contractor at this site. EPC contractors have a tough job and it requires a lot of good people working very hard to make money. When a contractor like this competes by cheating, it puts the respectable firms at a disadvantage. Philosophically, will the market punish this type of behavior? It’s not likely, because while this is an extreme reputation problem for the contractor, the owner is not likely to want this to be broadly known, and the OE involved also is not keen to broadcast their involvement. The owner will take a very large financial hit, a cover story will evolve, and most everyone involved will forget about it quickly.

Our view is that the lesson must be available for people to learn. That said, it is not our role to name the contractor or others because that would get in the way of knowledge transfer which is the goal here.

Savings from less rework and use of less skilled welders. Maybe $1mm. Cost to reweld all the large-bore in a huge power plant…??

Repair cost to the EPC contractor was immense, but the cost to the Owner was far greater due to the extended outages which persisted many years while O&M was trying to run the facility. This was well over a $100mm problem to the Owner the 1st year alone.